Collection in Context: Text-Based

Barbara Jones-Hogu, One People Unite, 1969. Screenprint on gold paperboard, 22 1/2 in. (57.2 x 71.1 cm). Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee 2018.17

Barbara Jones-Hogu, One People Unite, 1969. Screenprint on gold paperboard, 22 1/2 in. (57.2 x 71.1 cm). Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee 2018.17

In fall 2023, we debut our new brand identity, which uses text to give voice to Black artistic expression. In support of its launch, Curatorial Assistant Kiki Teshome writes about some of the text-based works in the Studio Museum’s permanent collection.

Art museum visitors often divide themselves into two categories: those who take time to carefully view the artwork first and those who diligently read the label description next to the artwork first. On special occasions, there are artworks that inspire both viewing and reading at the same time. How does one “read” a work of art? What makes a work of art legible? Text-based artworks describe works of art that heavily feature the written word and characters. These works use text as material—to explore form, add meaning, or reference other written sources. The following artists are just a few who complicate the understanding of both text and image as disparate categories serving distinct purposes, but which can be combined for a hard-hitting effect.

The artists of AfriCOBRA use text as material to explore form and political meaning-making. Establishing themselves in 1968 as a group with a penchant for language (“AfriCOBRA” is an abbreviation for African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), the collective recognized the saliency of making their messages for Black liberation accessible, appealing, and galvanizing. Founding artist Barbara Jones-Hogu’s One People Unite (1969) combines bold, graphic text and Afrocentric imagery in an arrangement that exemplifies the collectivizing demands and creative experimentation of the Black Arts Movement. The imperfect symmetry demonstrates how Jones-Hogu plays with geometric forms inspired by African visual aesthetics: interior shapes are filled in with color on one side and left blank on the other, words resist standard alignment and follow rounded edges, and letters transform into other symbols. By cleverly reconfiguring a face to represent three profile views, Jones-Hogu evokes the multitudes of Black communities. As a testament to their commitment to accessibility, the collective produced mass prints of the works to be distributed as posters that could live in people’s homes. In 1970, AfriCOBRA’s first exhibition took place at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary, 1972. Courtesy the artist and Kavi Gupta

AfriCOBRA founding member Wadsworth Jarrell similarly conveys the political urgency of the civil rights movement in his work Revolutionary (1972). This portrait of activist and intellectual Angela Davis is fashioned out of words from her speeches. Color and composition inform the artist’s placement of the densely outlined letters, where words rendered in dark blue ink delineate Davis’s iconic afro and spill out over the rest of the paper. The content and impact of Davis’s passionate speeches are visually reproduced in a manner that reflects how the legacies of intellectual and political luminaries are remembered just as much through their image as their words.

Contemporary artist Bethany Collins takes a different turn in her works, dealing directly with text in black-and-white to visualize personal connection and political exclusion. She reveals what text can communicate by removing words from a page. In Southern Review, 1987 (2014), Collins presents a grid of tear sheets from the literary magazine of the same name, published through Louisiana State University Press. The pages are covered in light fingerprints and dense rectangles of charcoal ink—used by the artist to redact passages except for moments in which Black cultural figures and allied patrons are mentioned—including Elizabeth Alexander, Carl Van Vechten, and Derek Walcott. The remaining visible lines of text are sparse. By arranging these redacted pages into a grid, the exclusion appears direct and confrontational.

Ellen Gallagher, Deluxe, 2004–05. Grid of sixty photogravure, etching, aquatint and drypoints with lithography, screenprint, embossing, tattoo-machine engraving, laser cutting and chine collé; some with additions of Plasticine, paper collage, enamel, varnish, gouache, pencil, oil, polymer, watercolor, pomade, velvet, glitter, crystals, foil paper, gold leaf, toy eyeballs and imitation ice cubes; Previously: Portfolio of 60 etchings with photogravure, spitbite, collage, laser cutting, silkscreen, offset lithography, hand painting, and plasticine sculptural additions

Each: 13 × 10 1/2 in. (33 × 26.7 cm)

Overall: 86 × 179 in. (218.4 × 454.7 cm)

The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase made possible by a gift from Thomas H. Lee and Ann Tenenbaum, New York

Like Collins, many artists use external sources for their text-based works by either appropriating printed material or directly citing other texts. Ellen Gallagher’s DeLuxe (2004–05) features a series of prints that recreate and modify advertisements for beauty products from Black magazines of the mid-twentieth century. The artwork emblematizes the artist’s larger practice of pulling from the formal strategies of commercial print media to experiment with different printmaking techniques. By collaging different images or adding her own illustrations and decorative elements, Gallagher simultaneously preserves archival material and recomposes print media. The resulting eccentric transformations undercut the serious nature of their past existence as marketing materials promoting beauty standards of their time.

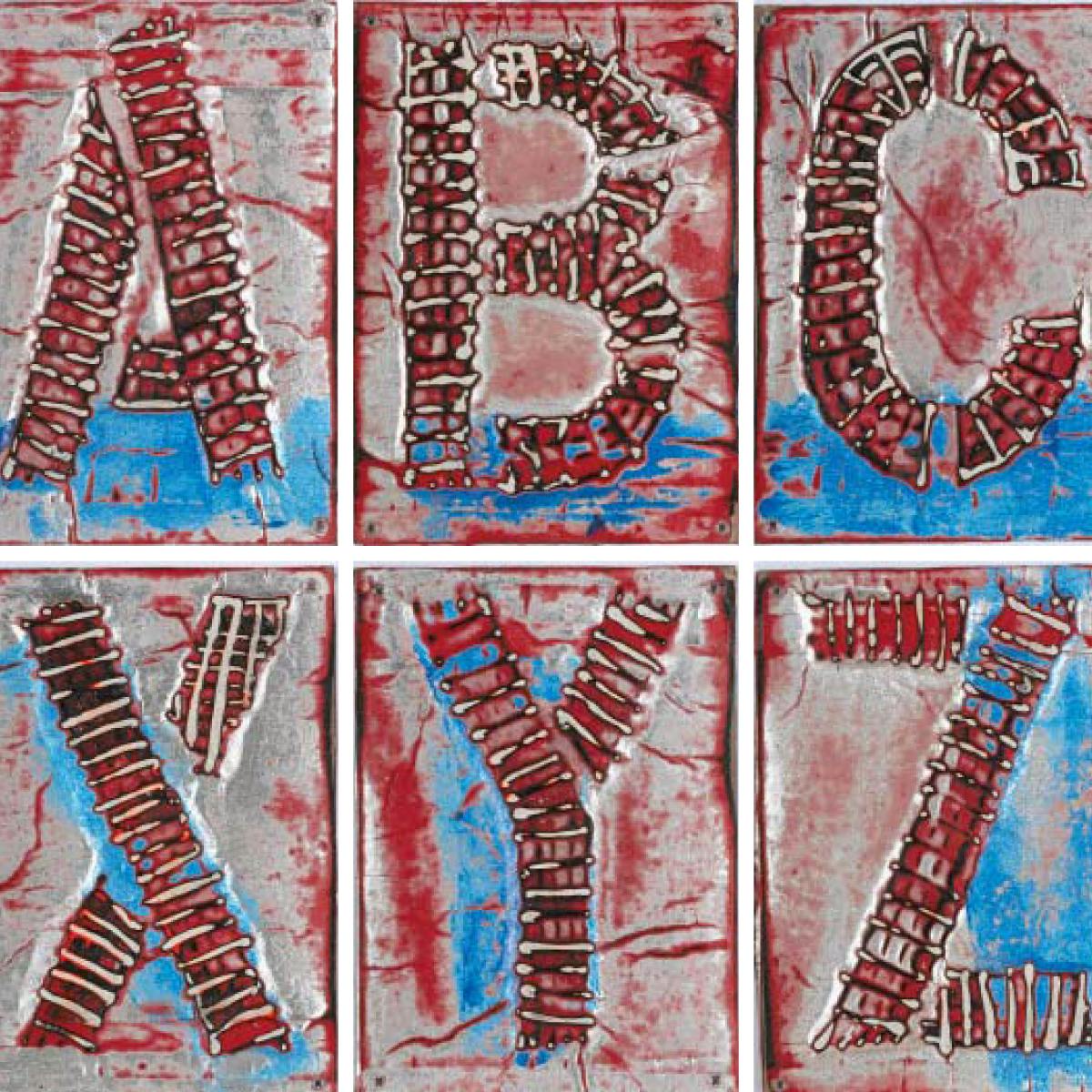

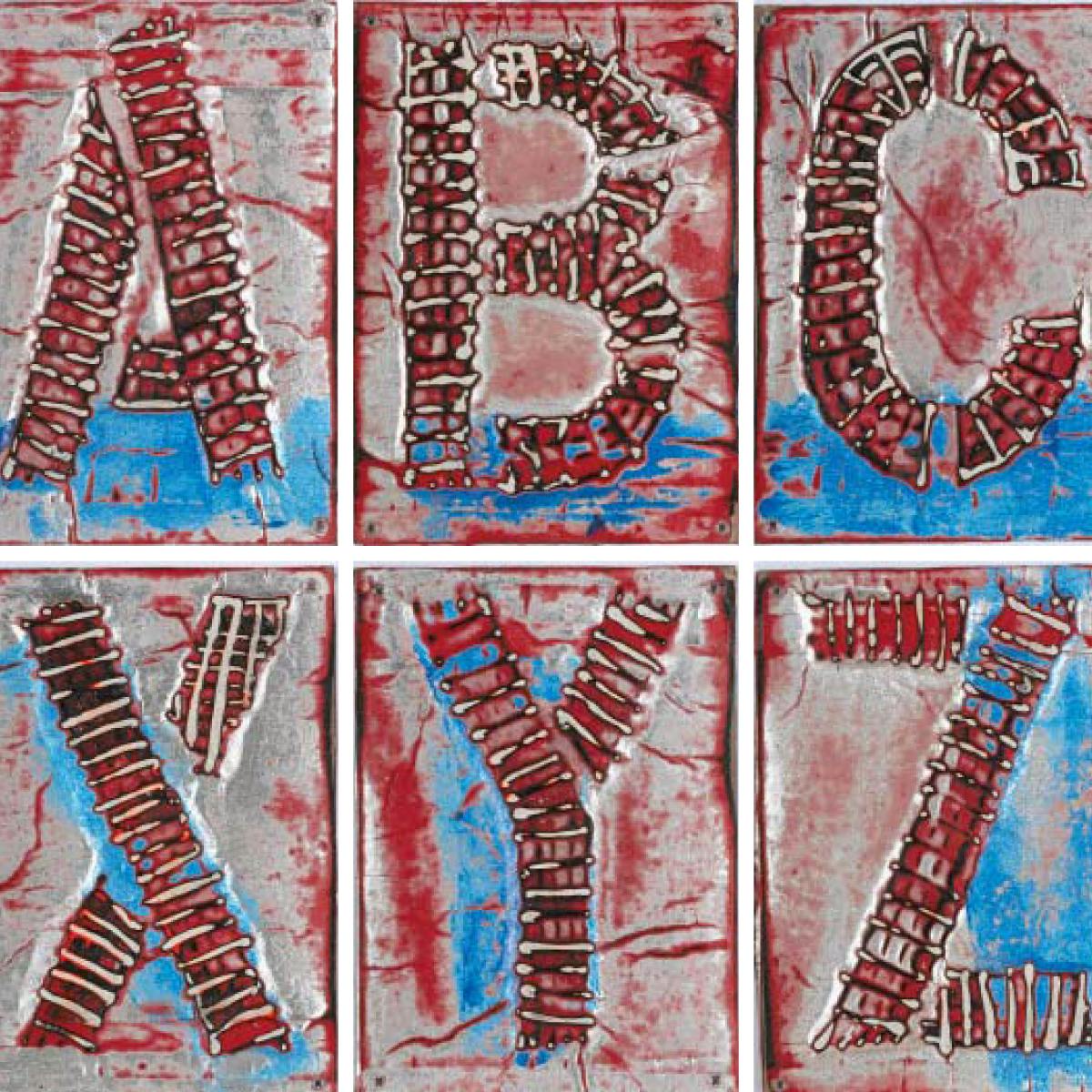

Mark Bradford, Untitled (A-Z), 2010

Mixed media collages on paper

The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase

2012.41a-z

The power of text-based art depends on the perceived function of language. Most text-based works in the Studio Museum’s collection appear in English and their legibility varies depending on familiarity with the language. Mark Bradford’s Untitled (A-Z) (2010) illustrates the building blocks of the language that features prominently in his artistic practice. Bradford is known for collecting posters in his neighborhood of South Los Angeles. He then deconstructs and repurposes these into large-scale works displaying messages that speak to the needs of his community. In this series, however, he intimately engages with the alphabet through a set of twenty-six small-scale décollage paintings that each feature a different letter in the English alphabet in bold red, white, and blue.

Charles Gaines, Randomized Text, History of Stars #2, 2006

Digital print and color pencil on paper

54 1/2 x 22 1/2 in.

The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee

2007.21

Since the late 1970s, Charles Gaines has been best known for his conceptual practice of combining seemingly unrelated materials from a wide range of disciplines to produce drawings, photographs, and installations that consider the subjective act of meaning-making. As the artist once described, “All of the letters of the alphabet can be combined to form meaningful words, but while you’re reading words in a meaningful way, you don’t lose sight of the fact that they’re made up of a limited set of symbols … Language becomes meaningful because we assign combinatorial rules to letter sequences. We are not aware of the infinite number of possibilities that could happen because they are being limited by the rules, and the rules themselves are arbitrary because they are social conventions.”[1]

In Randomized Text, History of Stars #2 (2006), Gaines places an image of the night sky above phrases of text. The phrases are randomly sequenced sentences from Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and Edward Said’s Orientalism. The resulting paragraph possesses a nonsensical, poetic quality and, when paired with the image of the night sky, complicates the expectation that image captions supply meaning.

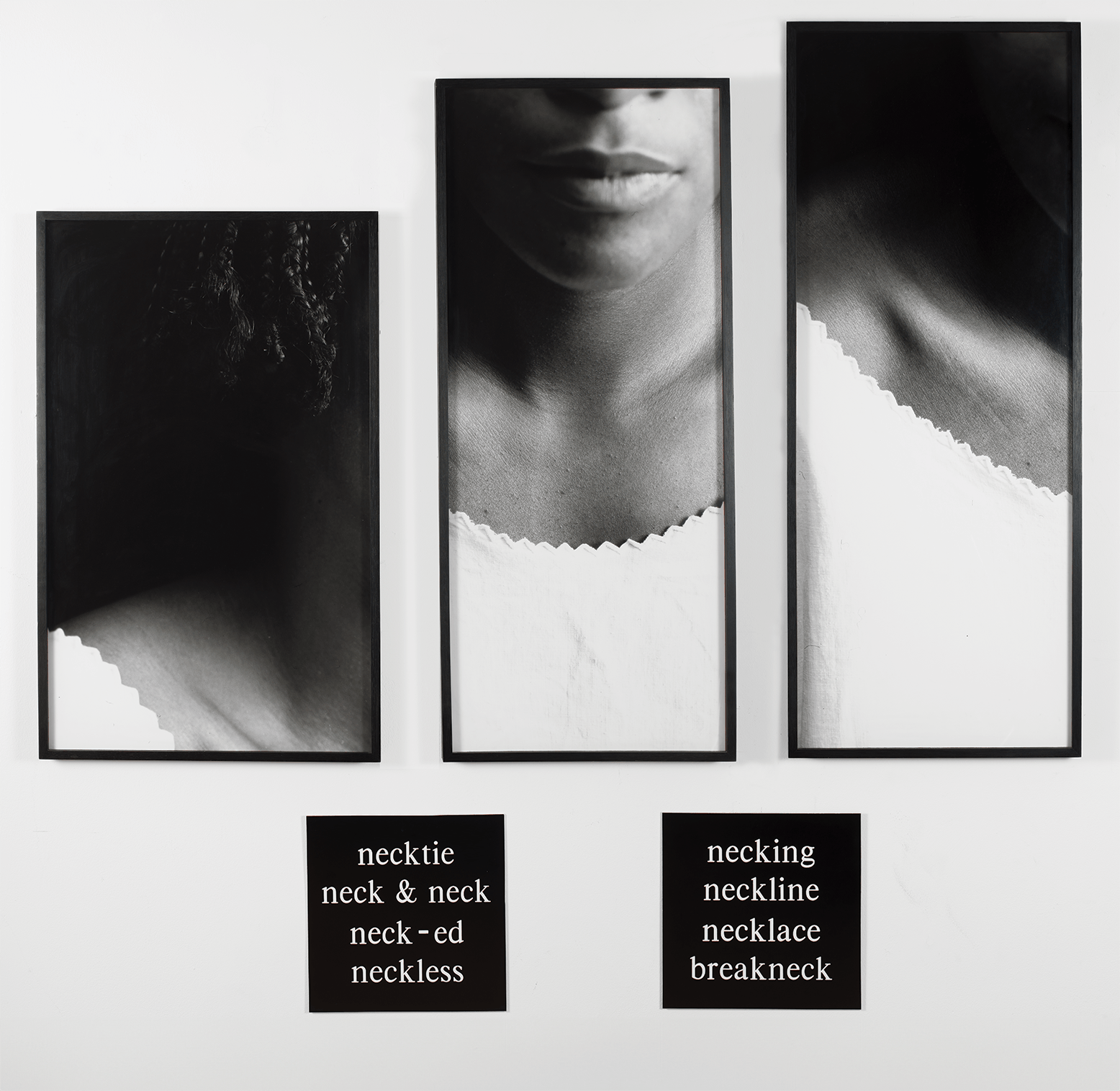

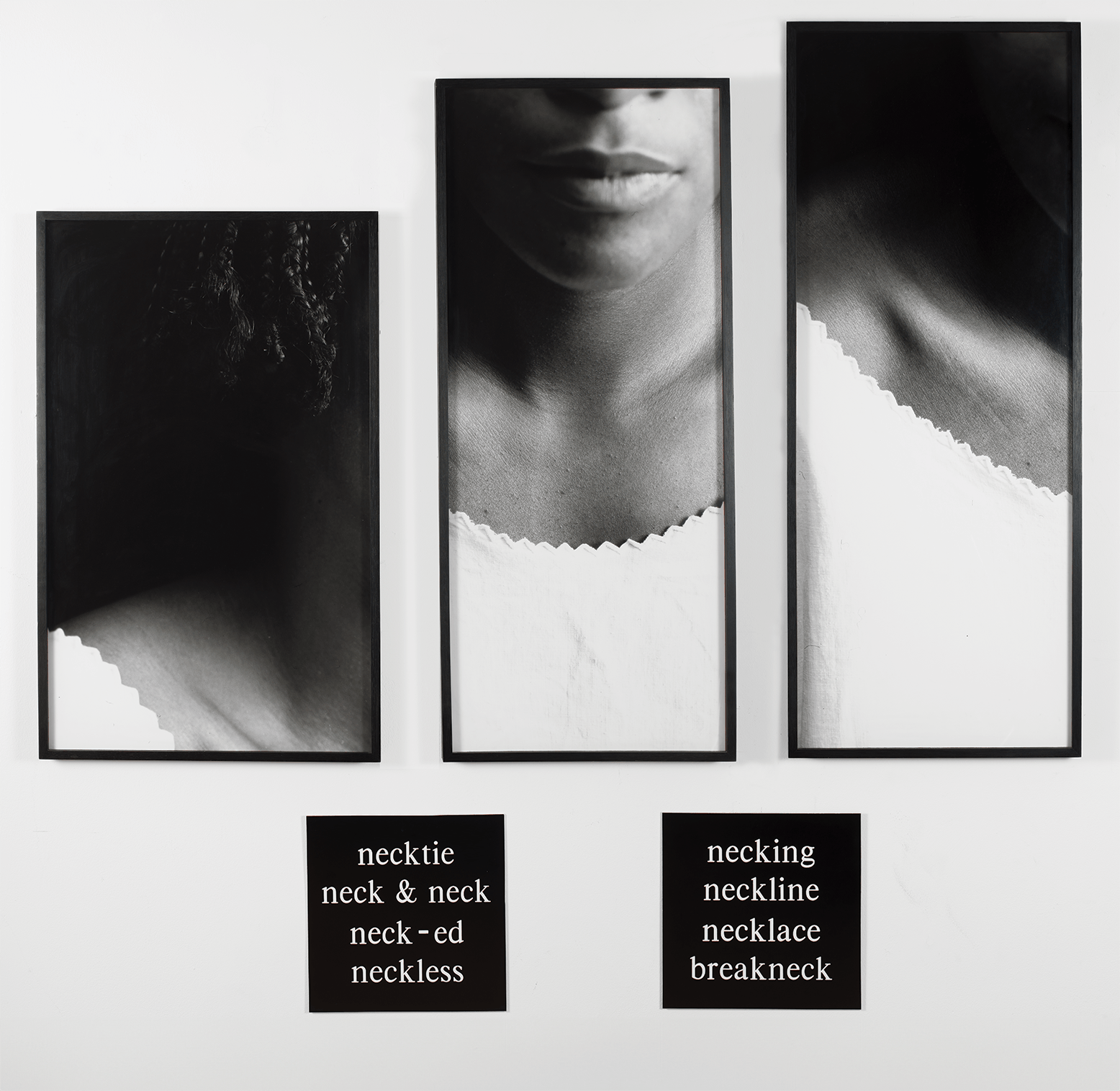

Lorna Simpson, Necklines, 1989.

Three silver gelatin prints, two engraved plastic plaques

69 3/8 x 67 5/8 x 1 5/8 in.

The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Emily and Jerry Spiegel, New York

2003.2.5a-e

Similarly challenging the associations made between image and text is noted artist Lorna Simpson. Since the 1980s, Simpson’s work has examined gender, race, and representation and the social constructions that inform the interpretation of each. Her most recognizable works are large-scale photo-and-text pieces that combine images of unidentifiable Black women with fragmented text. In Necklines (1989), the artist pairs three black-and-white images displaying different perspectives of a woman’s neck above two columns of text listing words that begin with “neck”. The words direct the viewers’ attention to the subject’s body. As a poet herself, Simpson’s selection of words is not just a haphazard verbal association but intentionally demonstrates the tension between language and image, symbol and signifier, race and representation. The sensitive, focused lighting on the subject, juxtaposed against these aggressive terms (“neck & neck,” “breakneck”) emphasizes the vulnerability of her body—and acknowledges the histories of violence toward Black people.

Glenn Ligon, Give Us a Poem, 2007.

Black PVC and white neon. 75 ⅝ x 74 1/4 in.

Studio Museum in Harlem; Gift of Glenn Ligon. 200 7.32. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Thomas Dane, London, and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.

Photo: Farzad Owrang

Text-based works can invite multiple readings and inspire new ways of considering legibility. Artist Glenn Ligon plays with the deceptively simple uses of language in his neon work Give Us A Poem (2007). Ligon is best known for his practice of citing literary references and exploring their presentation in black-and-white across painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation. In this work, the artist references a lecture given by Muhammad Ali at Harvard University in 1975. When asked by a student to give the audience a poem, Ali responded succinctly with the words “Me We.” Here, the poem and its powerful invocation of the individual and the collective shines brightly.

As seen in these works, artists incorporate text in their works for a variety of purposes. While some mine the conceptual or graphic possibilities of language, others are more direct and wield language as a further extension of asserting their visual expression.

[1] Paul Soto, “Infinite Re-Combination, Q+A with Charles Gaines,” Art in America, September 9, 2011, www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/charles-gaines-susan-vielmetter-56221/.