Silhouette

04.11-07.01.2007

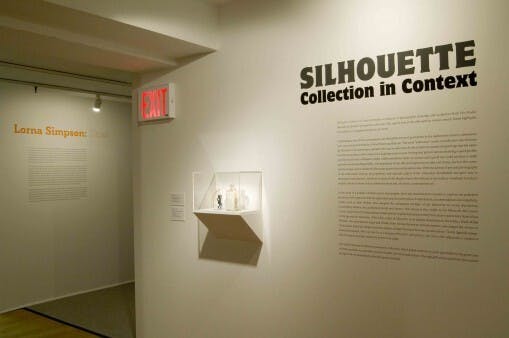

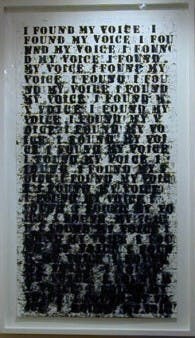

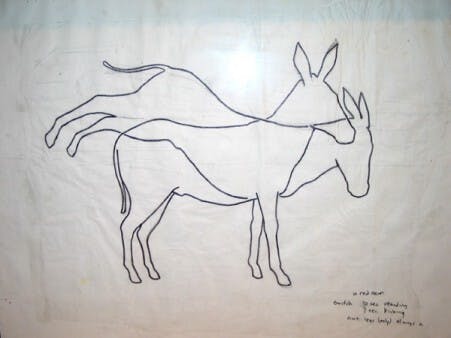

Silhouette: Collection in Context presents a selection of photographs, drawings and sculptures from The Studio Museum in Harlem’s permanent collection. This topical look at the silhouette in various artistic forms highlights its potential as a poignant and poetic art form.

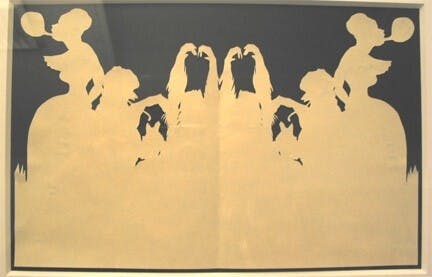

Originating as one of the most popular and affordable forms of portraiture in the eighteenth century, silhouettes were very common in both the United States and Europe. The word “silhouette” can be traced back to the Étienne de Silhouette, a French finance minister who was so notorious for his attacks on wealth and privilege that his name became synonymous with inexpensive duplication processes. During that period, anyone desiring a quick profile portrait would visit a silhouette artist; within moments, a pair of scissors and a good eye could produce a small portrait with astonishing fidelity. The popularity of the silhouette gave way to other art forms, such as the cameo and the intaglio, which rendered silhouettes in precious metals and stones. With the advent of portrait photography in the nineteenth century, the popularity and cultural capital of the silhouette diminished and gave way to mechanical reproduction. However, in spite of this displacement, the silhouette has made a comeback in today’s popular culture in music videos, advertisements and, of course, contemporary art.

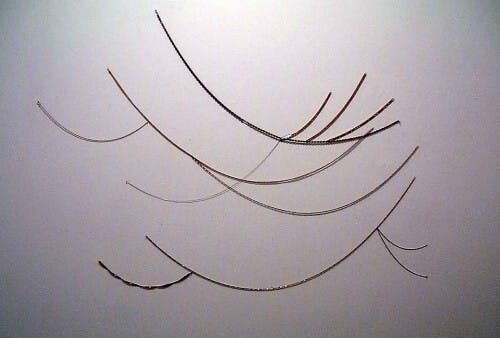

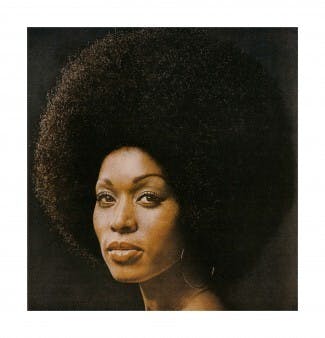

In the work of a number of Black artists, this graphic form has resurfaced as a means to explore the polarized positions of the oppressor and the oppressed, and the power plays of exploitation, accommodation and complicity. Artists, such as Kara Walker, have adopted the antiquated medium of the silhouette to revive discussions surrounding identity, the antebellum South and slavery. This theme is also visible in For Whom the Bell Curves (2006), Robert Pruitt’s wall sculpture made entirely of gold chains that loosely trace slave trade routes from Africa to Europe and the Americas. (This work, a part of Silhouette, is on display downstairs in the lobby.) Hank Willis Thomas, who manipulates logos and brands from African-American advertisements, encourages the viewer to “look harder and think deeper about the empire of signs that have become second nature.” In his digitally manipulated photograph, Who Can Say No to a Gorgeous Brunette? (1970/2007), the 1970s afro silhouette, a symbol of African-American pride, retains its power even today.

The Studio Museum in Harlem’s permanent collection, which began nearly forty years ago thanks to the generosity of artists and donors, currently consists of nearly two-thousand objects. Through gifts and acquisitions, the number of objects in our permanent collection grows annually.

Silhouette

04.11-07.01.2007

Silhouette: Collection in Context presents a selection of photographs, drawings and sculptures from The Studio Museum in Harlem’s permanent collection. This topical look at the silhouette in various artistic forms highlights its potential as a poignant and poetic art form.

Originating as one of the most popular and affordable forms of portraiture in the eighteenth century, silhouettes were very common in both the United States and Europe. The word “silhouette” can be traced back to the Étienne de Silhouette, a French finance minister who was so notorious for his attacks on wealth and privilege that his name became synonymous with inexpensive duplication processes. During that period, anyone desiring a quick profile portrait would visit a silhouette artist; within moments, a pair of scissors and a good eye could produce a small portrait with astonishing fidelity. The popularity of the silhouette gave way to other art forms, such as the cameo and the intaglio, which rendered silhouettes in precious metals and stones. With the advent of portrait photography in the nineteenth century, the popularity and cultural capital of the silhouette diminished and gave way to mechanical reproduction. However, in spite of this displacement, the silhouette has made a comeback in today’s popular culture in music videos, advertisements and, of course, contemporary art.

In the work of a number of Black artists, this graphic form has resurfaced as a means to explore the polarized positions of the oppressor and the oppressed, and the power plays of exploitation, accommodation and complicity. Artists, such as Kara Walker, have adopted the antiquated medium of the silhouette to revive discussions surrounding identity, the antebellum South and slavery. This theme is also visible in For Whom the Bell Curves (2006), Robert Pruitt’s wall sculpture made entirely of gold chains that loosely trace slave trade routes from Africa to Europe and the Americas. (This work, a part of Silhouette, is on display downstairs in the lobby.) Hank Willis Thomas, who manipulates logos and brands from African-American advertisements, encourages the viewer to “look harder and think deeper about the empire of signs that have become second nature.” In his digitally manipulated photograph, Who Can Say No to a Gorgeous Brunette? (1970/2007), the 1970s afro silhouette, a symbol of African-American pride, retains its power even today.

The Studio Museum in Harlem’s permanent collection, which began nearly forty years ago thanks to the generosity of artists and donors, currently consists of nearly two-thousand objects. Through gifts and acquisitions, the number of objects in our permanent collection grows annually.