Allegories

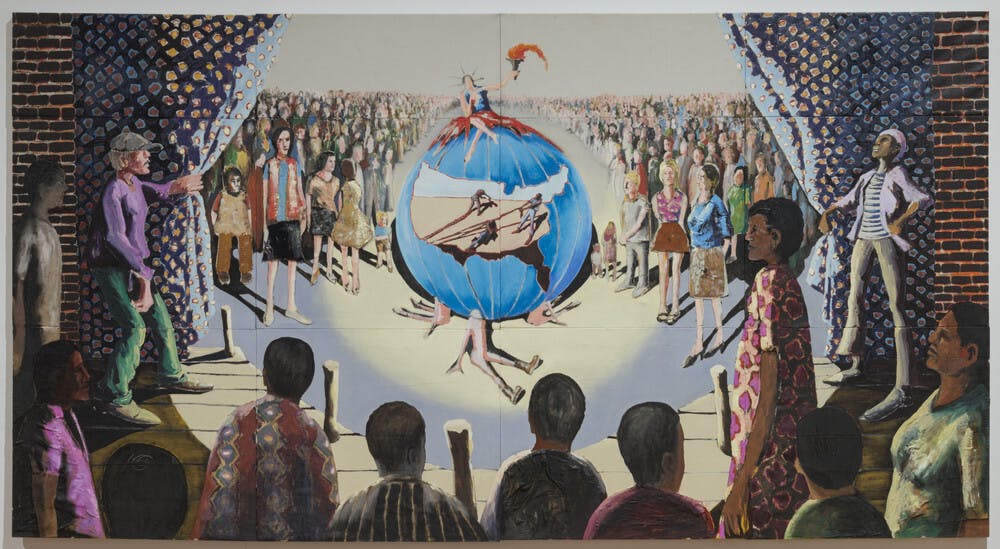

These artworks reinterpret and reimagine common allegories, often to relay stories related to Black experience. A literary and visual device, allegories explain, shape, and resonate with the human experience by revealing a message, usually moral or political. They convey meaning by relying on established and easily understood symbols and characters—often personifications of human ideas or qualities—such as fortune, peace, virtue, and victory.

As seen in these works, allegories have long served as artistic inspiration, points of departure, and opportunities for contemporary commentary. Artists of African descent have incorporated various allegories to communicate experiences, frustrations, ideas, and lessons related to the world they live in. By drawing on widely understood symbols and personifications, their works broaden access, encouraging viewers to participate in the interpretation of their meanings.

Allegories was organized by Connie H. Choi, Curator.

“The Bicentennial Series” preemptively responded to what Benny Andrews predicted would be the near-exclusion of Black American history and contributions from the US bicentennial celebrations. Trash depicts a caravan of society’s ills and so-called values being carted to a dumping ground by three Black figures.

Andrews uses allegory to comment on the state of the nation.

The allegorical figure Lady Liberty is depicted nonchalantly enjoying a lollipop while phallic, headless bodies with military helmets on their severed necks sit lifeless beneath her. Andrews utilized such symbols and personifications to express his contempt for US politics and society.

In the top left corner of Trash, a seated figure in a military uniform steps on the US coat of arms while holding a bindle of hundreds of naked bodies, perhaps alluding to the human toll of the war at the hands of armchair generals.

This work features a more enigmatic use of the allegorical figure.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller sculpted lowered eyes and a stoic expression on this figure, which might be translated as a visual representation of centuries of silencing of people of African descent, or a form of strength and resilience—a way to deny the viewer access to her innermost thoughts and feelings.

Hale Woodruff applies the tradition of personifying the continents in this work.

He revises the Greek myth of Europa by replacing Europa, for whom the continent of Europe is named, with that of Africa, depicted as a Black woman on the back of a large white bull. Africa’s position symbolizes the rape of both the continent and its people, offering a sobering reading to the myth.

Some artists use allegories to insert Black figures into classical narratives.

Daphne references the myth of the naiad, often interpreted as an allegory of chastity. In Elizabeth Colomba's vision of the story, Daphne doesn't flee from the god Apollo; instead, she stands her ground, becoming an allegory of female strength.

African American oral traditions.

In the story of the Br’er Rabbit, the titular rabbit finds himself caught by his nemesis Br’er Fox, but outwits his captor and gains freedom. The plane in this sculpture does not appear to have the same luck. It can be viewed as an allegory of Black struggle—freedom is possible, but it only comes after immense sacrifice.

As seen in these works, allegories have long served as artistic inspiration, points of departure, and opportunities for contemporary commentary. Artists of African descent have incorporated various allegories to communicate experiences, frustrations, ideas, and lessons related to the world they live in. By drawing on widely understood symbols and personifications, their works broaden access, encouraging viewers to participate in the interpretation of their meanings.

Allegories was organized by Connie H. Choi, Curator.