Genesis Jerez: (Family) Record of Imagination

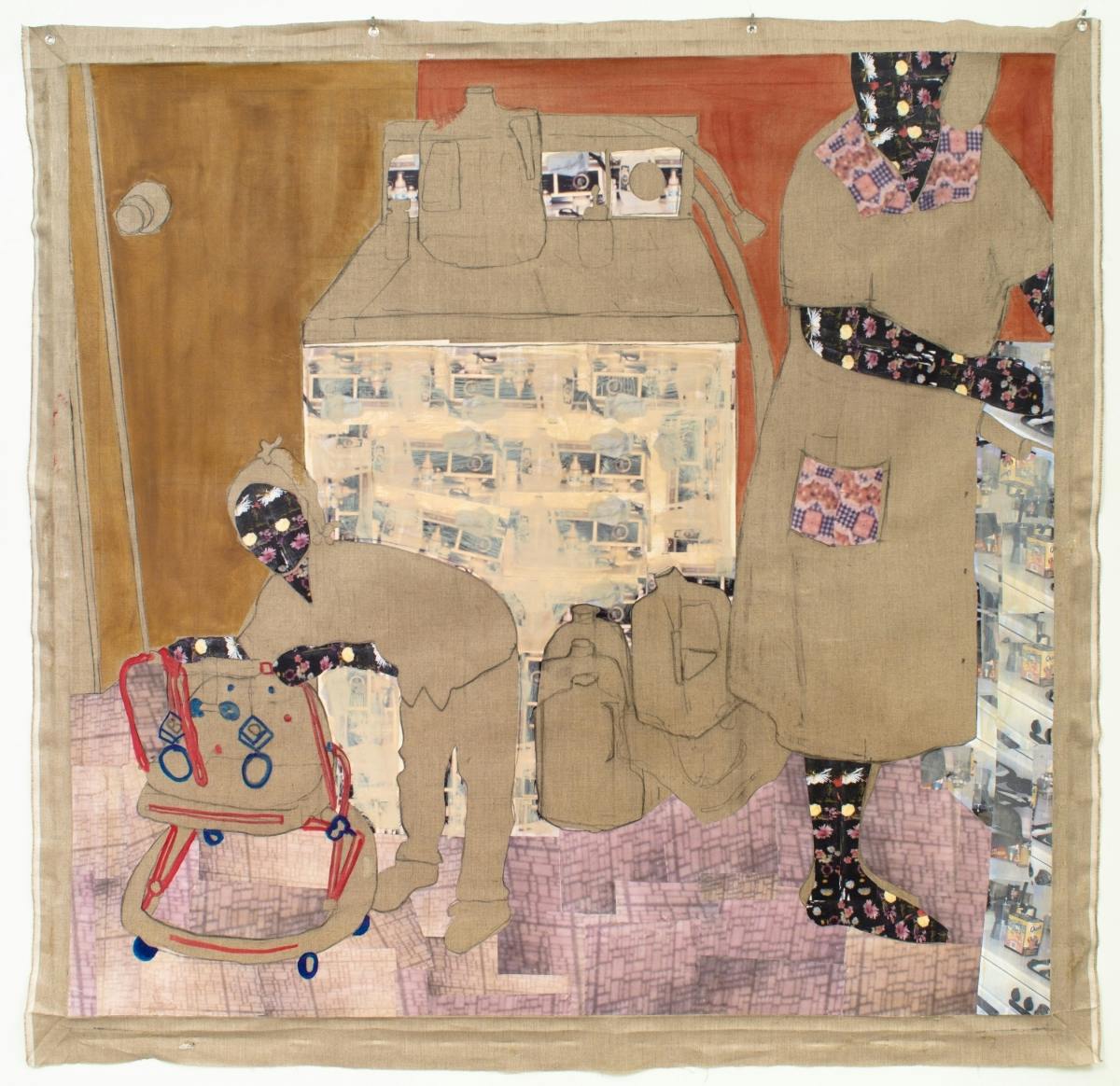

In Genesis Jerez’s mixed-media paintings, there is an ongoing mediation between formalist concerns and the demands of deeply personal subject matter. This careful arbitration embeds itself in works such as Mother in the Kitchen (2020). In this piece, the artist’s material and compositional decisions intercede on a scene of family life sourced from her family’s photographic archive. For Jerez, these photographs provide visual material to be evaluated and then used in multiple ways to compose an image that centers not the artist’s perspective, but that of her mother who orchestrated and preserved these moments. Jerez reconstructs a kitchen scene of a mother (the artist’s) and a child (the artist’s older sister) using photographs, or elements from these photographs, printed on photocopy paper, oil paint, and underdrawings on linen. Our gaze moves through the visual material on display—the floral collage patterned faces and limbs of the two figures, the loosely drawn gallon containers on lilac collage floors, and the collaged snapshots of a kitchen counter that form the scene’s kitchen cabinets where the mother is at work, a motif of cafeteras (stovetop coffee makers) and canned goods clearly visible. In Mother in the Kitchen, Jerez’s attention to material choices, balance, flatness, and composition mediates the task of negotiating complex familial relationships and the transformations of these bonds over time.

In her time in the 2020–2021 Artist-in-Residence program at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Jerez continues to reflect on the body of work she has been developing for the past few years. The artist’s art school experience in New York City was a period of experimentation, which included using found materials in what she jokingly calls her “Rauschenberg phase,” to working on figurative oil paintings. After graduating, she entered a critical period of both personal and professional self-evaluation. “Since graduating, instead of going to grad school— my interest grew more toward residencies— I’ve been spending time deconstructing myself and peeling layers of trauma, poverty, and survival while developing this work,” Jerez says. This deconstruction involved, on one hand, challenging personal decisions (stepping away from family), and on the other, reexamining her art education and practice. From this place of reevaluation, her current work materializes.

“The work feels instinctive, it makes itself,” Jerez says— but don’t be fooled, “The work feels instinctive only because I’m using my life experience as a resource and have gotten to a point where I’m giving the work what it needs to be good, what it needs to survive.” Every decision on the linen surfaces of Jerez’s works has been analyzed, and if found wanting is deconstructed and reconsidered in future works. With photographs taken from her family archive, Jerez at times uses the composition and elements of one or two images to create familiar and unfamiliar spaces, extracting nostalgic patterns and textures, architectural details, and, of course, the figures. Interestingly, Jerez explains most of these images are not really hers; they capture a time before she was born or during her very early years, and center her older siblings’ childhoods. The perspective shifts, and the artist becomes an outsider looking into her own family. As these photographs capture family moments from her mother’s perspective, or that of another family member’s, the artist is aware her mixed-media paintings provide a platform of sorts, for her mother’s life, and asks “How do I make sense of it and honor her life through this body of work?”

In the process of experimentation, Jerez realized de facto painting— figures, patterns, apartment environments— wasn’t the right approach at the moment. Collage, which features prominently in her work, comes from an affinity with the notion of flatness and provides a way to integrate her source images, further embedding them within a process of reconceptualizing family history and relationships. “I feel like the collaging, the way I am using collage … is really another way of painting,” she says. “I really like that it creates such a flat look, a sense of realism, because it’s essentially a photograph. It’s my way of bringing in the images I am using, so it has this sentimental value to me.” When paint does come into play, Jerez seeks flatness through its application.

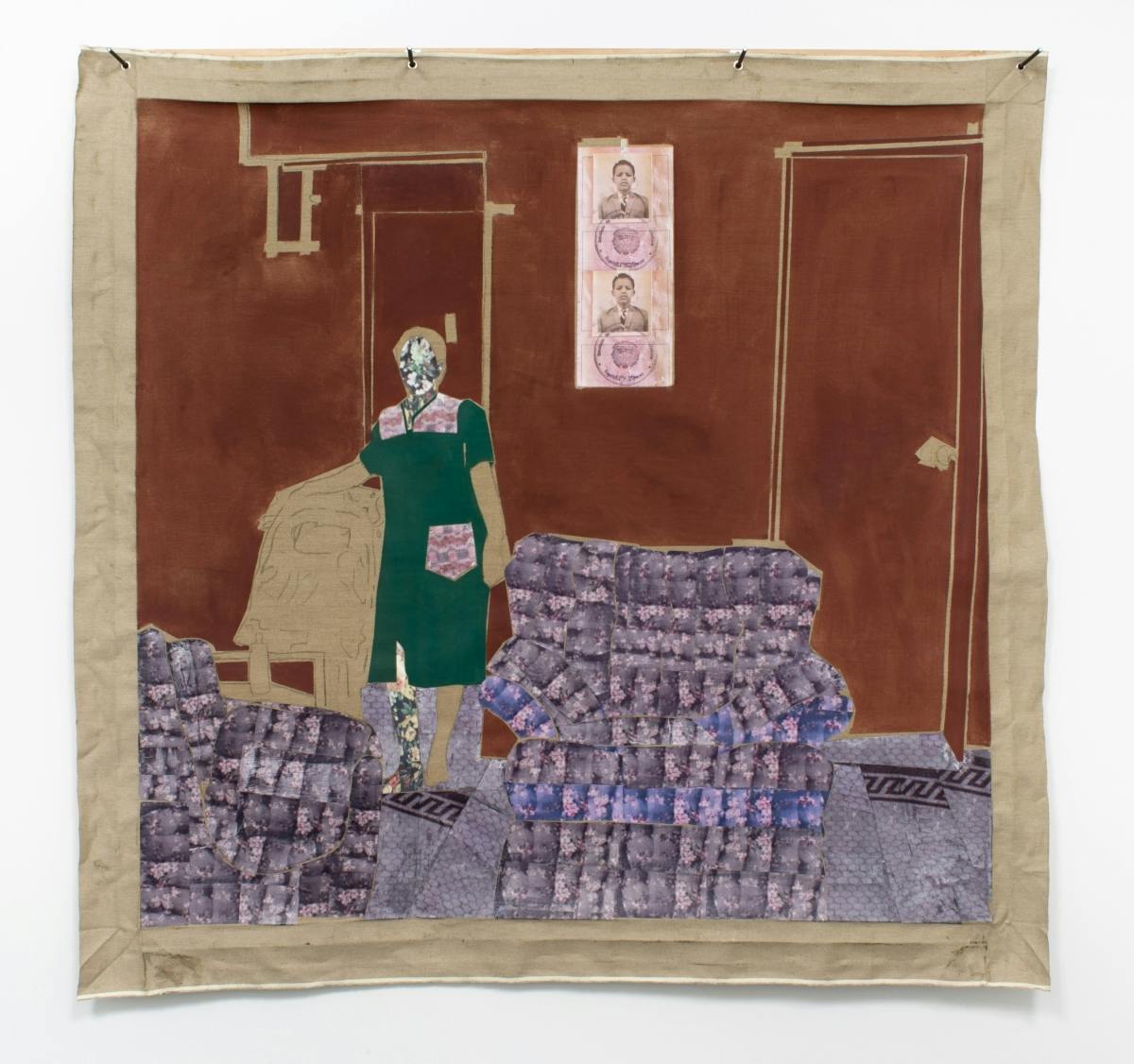

Using rags, she rubs the paint onto the linen to ensure it sinks in. “Painting,” Jerez says, “was a straightforward decision that made me want to integrate and think about other possibilities to give me what I wanted in the work.” But painting “traditionally” in a “painterly way,” as she describes it, has never ceased to be of interest. From works such as Oh, Father (2019) to more recent work like Watching over Her (2021), Jerez continues to work out her relationship with painting.

In our conversations, it became clear reconsidering her art training did not include severing or dismissing the active dialogue between her practice and that of other artists. “I like looking at good paintings and works. I am constantly learning from them. I enjoy places like the Barnes Foundation, which has a collection that I sincerely love, it holds so many wonderful works in one place, and it just makes me feel good. Artists like Kerry James Marshall, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Robert Rauschenberg, Eva Hesse, and more are some of whose works I look at every day. Someone like Egon Schiele, he made me love line, and I always thought a line in itself could be so beautiful and powerful; why paint it?” In this, there are lessons: Take what is needed, leave what is not.

Jerez reconsiders on linen the importance of the figure and the ways it can be presented. Family photographs supply visual material, but they are also reminders of personal trauma. As I spend time with Jerez’s work, I keep coming back to the artist’s decision to either use paper collage with patterns derived from the family photographs on a figure’s face and limbs blocking out details or to lightly sketch out faces and forms on the linen and leave them at that. These are necessary decisions that draw from the wealth of visual languages that feel appropriate to Jerez but are also part of a difficult healing process. “This is my way of giving my family some presence in my life, and I get to reimagine it,” she says. Material and technique provide the requisite distance needed to reconsider her source images and the weight they carry.

Her attention has also shifted to the environments depicted in these mixed-media paintings. Still drawing from photographs, Jerez considers her own history with public housing, the backdrop of many of these works. In works like Blue Ballerina (2021) and All Her Children (2021), among others, the artist incorporates and reexamines the aesthetics of the New York City public housing she grew up in, visited, and returned to. “Growing up and currently living in the projects,” notes Jerez, “with all its systematic faults, I use it as another source of material. The work is heavily influenced by public housing structures, colors, lack of color, feelings of despair, joy, and the many different lives it holds.” But the individuals within these spaces remain distinct, as Jerez offers to this family record an imagination and care truly of her own making, and rigorously continues interrogating the formal qualities and possibilities of painting.

In the artist’s process of ongoing improvement and contemplation, revelations abound. When discussing recent work, Jerez observes her sister’s appearances in these paintings were marked by visually similar floral patterns extracted from the photographs and printed on paper. “I think that might be her identity within these works,” she says (see Mother in the Kitchen, and also Blue Ballerina). Jerez has arrived at a place where these relatives are becoming characters who need their own identities within her work. Perhaps this approach allows the artist, expanding in her own selfhood, to meet family members for the very first time, or once again, removed from a family history.